Sylvia Earle, a pioneer of both deep sea diving and ocean conservation, has made it her mission to protect the ocean’s biodiversity, one spot at a time.

Despite celebrating her 88th birthday last August, Sylvia Earle seems to whirl around the globe faster than a hurricane gathering strength. She still travels about 300 days of the year and just returned from the Cayman Islands, Brazil, Mozambique, Mexico, Antarctica and Europe. “I feel like an octopus with all arms fully engaged,” she says about her workload. “If a child is about to fall off a 10-story building and you are in a position to catch it, you’ll do everything in your power to be positioned just so you can save it. You don’t look away and have a cup of tea in the meantime.”

Earle’s sense of urgency is due to her unique position in history. The first woman to dive with scuba gear in the early 1950s, the first person to walk on the ocean floor 1250 feet under the surface in 1979, the first female chief scientist of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 1990, she has explored the oceans deeper and longer than any other woman on the planet. This gave her a front-row seat to the changes occurring below the surface, long before women were welcomed in marine sciences.

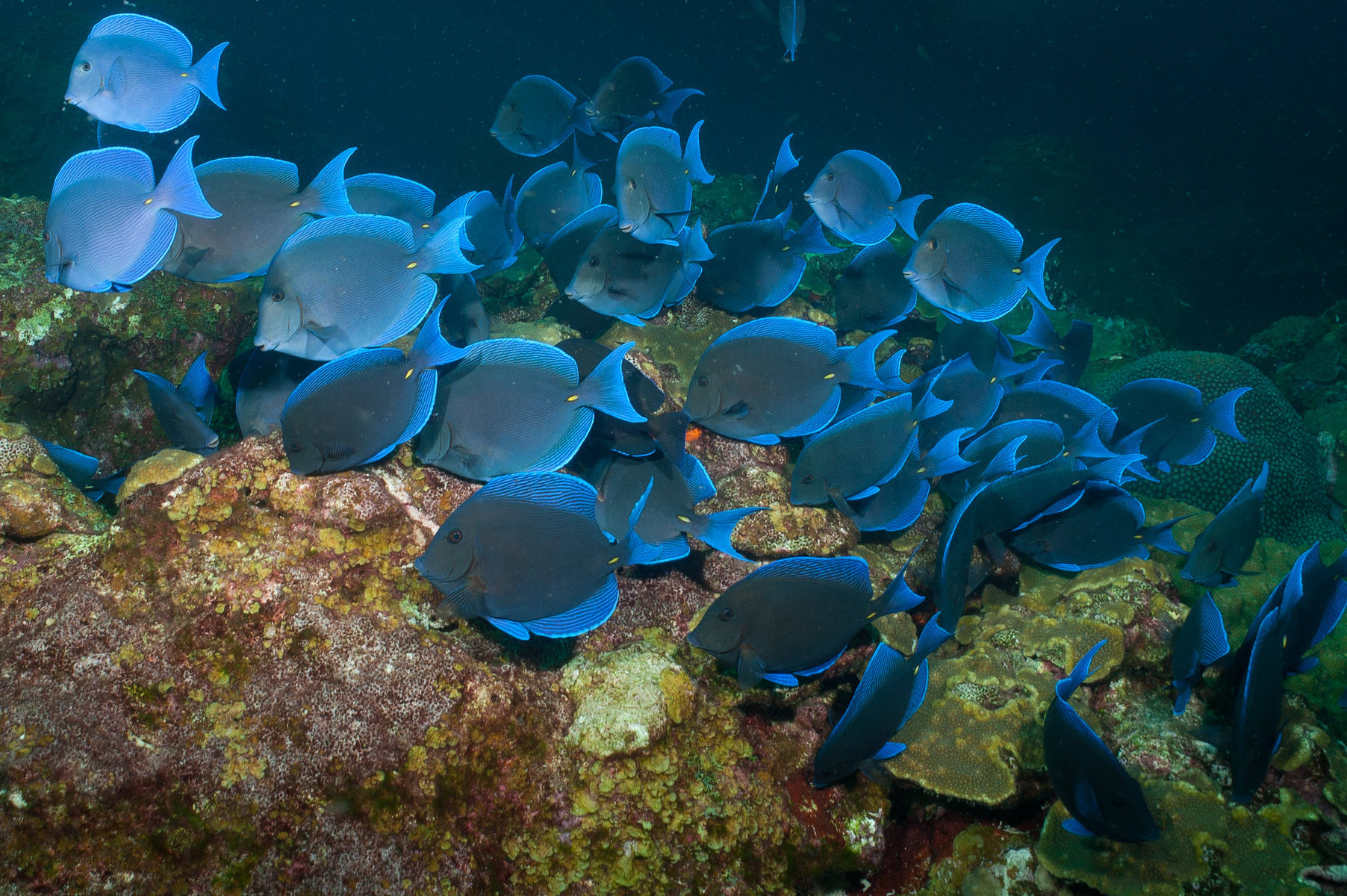

Now, when she returns to spots that once brimmed with fish and vibrant corals, she often only finds a gray underwater desert. While about 12 percent of the land around the world is under some form of protection, less than three percent of the ocean is protected.

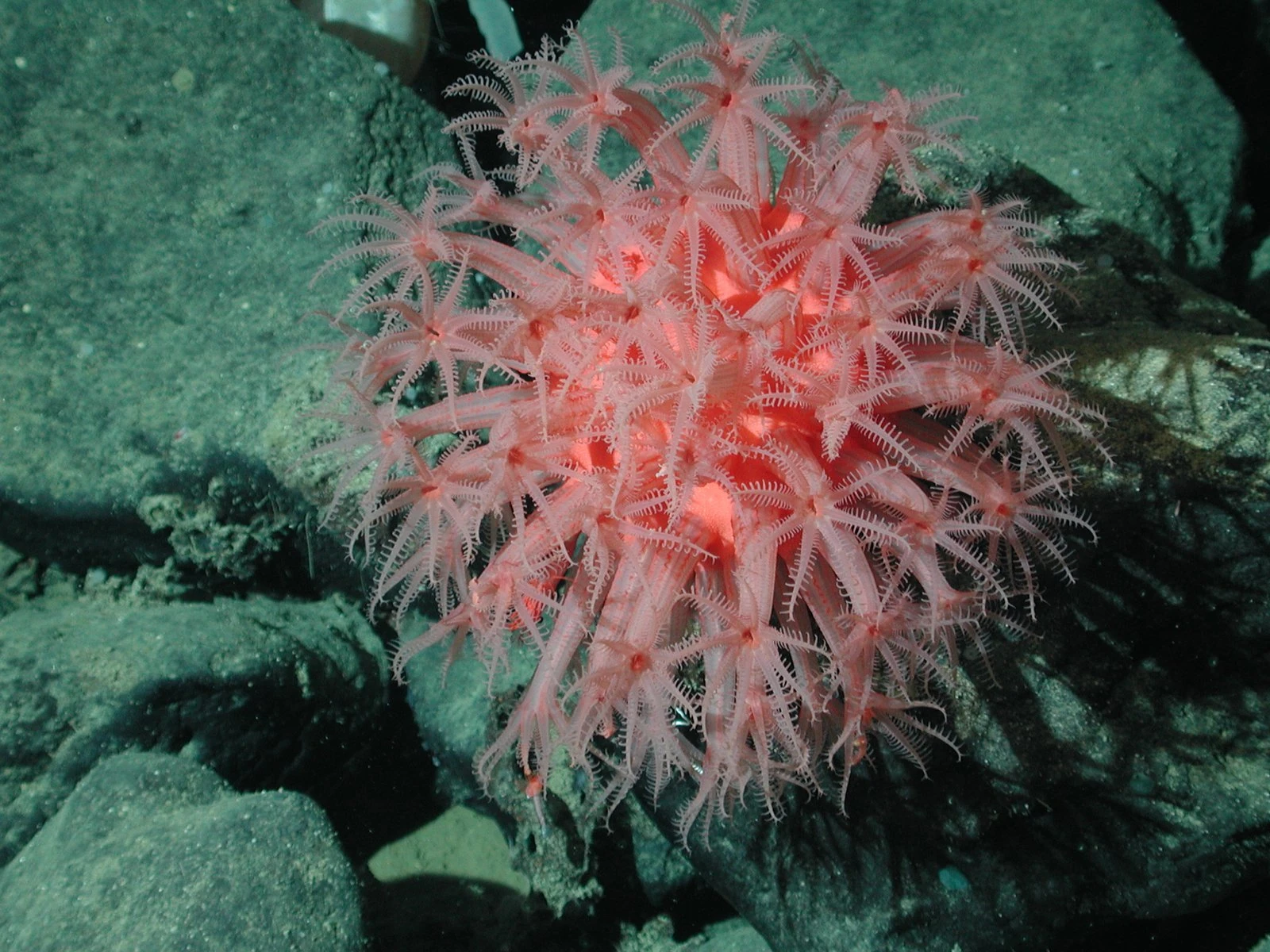

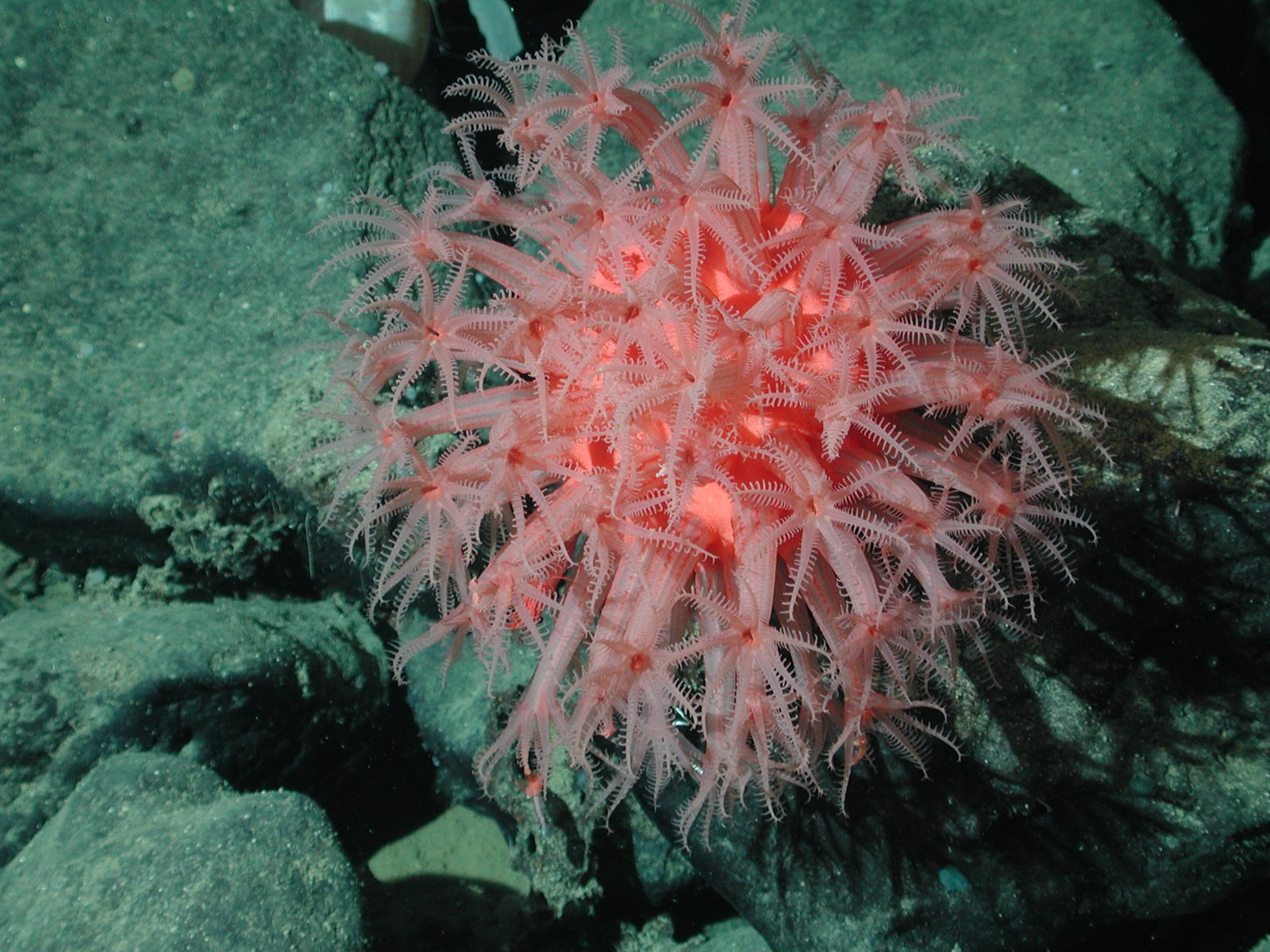

“Which means 97 percent are open for exploitation,” she says. “We have lost about 90 percent of sharks, tuna, and other fish, and 50 percent of coral.” “Her Deepness,” as the world’s most renowned marine scientist is lovingly called by friends and fans, has been working to change that. In 2009, she started the nonprofit Mission Blue with 19 Hope Spots, defined as “areas critical to ocean health in that they have a significant amount of biodiversity.”

There are now 158 Hope Spots, “and counting,” Shannon Rake, Mission Blue’s Hope Spot Manager, emphasizes. Hope Spots can be as large as the coral triangle in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Sea and as well-known as the Galapagos Islands, or small and quite unknown, like a dozen seamounts off California’s coast. No matter how tiny, Earle is convinced every Spot counts. “Every place, even the small places, makes a difference,“ she insists. “But we need to scale up. We need to get big. Take care of the ocean as if your life depends on it because it does.”

The Harvard-trained marine scientist with a PhD from Duke University has made it her mission to advocate for the ocean. Earle compares the ocean to our heart. “You wouldn’t say you need to protect just three percent or even 30 percent of your heart,” she says. “The oceans are the heart of the planet. Without it, life is not possible.”

Initially, Hope Spots were identified by renowned scientists. But after the 2014 Netflix documentary Mission Blue made her idea popular and people started reaching out to the nonprofit, Earle opened the process up to the public. “We’re overwhelmed by nominations from the public,” Rake admits before she adds, “in a good way!” She receives up to 100 nomination requests per year that are reviewed by a committee.

While Earle is petite in stature, she maintains a vigorous and outsized optimism. “I think you could get really depressed looking at headlines if you wished to focus on the bad news; there’s plenty of it,” she admits. “If we wait much longer to act on those opportunities we will lose the chance. So this is literally the best time that I can think of in all of history to be alive because just in my lifetime, I’ve witnessed greater insight, greater knowledge, about the fabric of life.”

One Hope Spot is literally just outside the windows of her Alameda, CA, office — the San Francisco Bay. “Admittedly, it’s not exactly pristine,” Earle comments, “but better than it has been in the past because people are coming together to take action and restore its health.”

When she started exploring the seas decades ago, humankind thought the oceans were so vast they could handle any amount of trash, toxic pollutants and fishing boats. Earle was among the first to sound the alarm.

She was also the one who pointed out that Google Maps should be called “Google Dirt” because it didn’t map the oceans, only the land. Google promptly expanded its program to map the blue.

Some Hope Spots are already fully protected marine areas, and the designation is meant to help keep the protections in place when governments change or funds dry up. At other times, the nomination process for a Hope Spot can help galvanize the support of local governments and environmentalists to put legal protections in place. “Mission Blue is trying to help the local communities and ocean champions to move the needle,” Rake says. “Then we’re trying to maintain that status because as we know, administrations change and can roll back policies. We’re using our collective power and community activism to let elected officials know how important this place is. No, you really shouldn’t build a timber port right here in the migratory pathway of endangered southern right whales. This allows the elected officials to learn more about what’s at stake and what the community wants.”

For instance, Cabo Pulmo in Mexico was so badly overfished that fishermen kept pulling empty nets from the sea. In the late 1990s, the fishing cooperatives joined forces with scientists, implemented fishing regulations and replaced income from fishing with ecotourism. Through Global Fishing Watch, Mission Blue observed fishing ships leaving the area after protections were put in place. “The tuna industry was very against [the no-take designation] because they thought their catch would decline but it ended up being the reverse,” Rake remembers. “They now see a 25 percent increase in their yield near the protected areas because of the spillover effect when you protect an area.”

The Palmahim Slide in Israel is another example of a Hope Spot that didn’t have any protection before it was nominated. The rare geological formation deep in the Mediterranean Sea, about 20 miles off the Coast of Tel Aviv, is a biodiversity hotspot where catsharks breed and bluefin tuna spawn. “We helped the marine conservationists with letters of support, scientific advisory and communication, and they were able to create a protected area approved by government officials,” Rake explains. “We’re using our international spotlight to really push for protection in these areas.”

“Every Hope Spot is on a different journey,” Rake says, referring to widely varying local regulations. She mentions Shinnecock Bay on Long Island’s South Shore as another example where the Hope Spot designation had a measurable impact. “It was severely degraded, was having red and brown tides,” Rake says. “There has been an absolute incredible change, doing restoration work with clams and oysters.”

Earle’s favorite Hope Spot might be the Gulf of Mexico. Earle was 12 when her parents moved the family from New Jersey to a beach house in Florida. The ocean became her playground. “It’s where I first took the plunge as a kid and saw what life is like underwater.” It was also in Florida that she first became aware that nature was being destroyed for human consumption.

Mission Blue cooperates with more than 200 ocean conservation groups worldwide, aiming to galvanize local, regional, national and international protection. Some are well known, such as the Ocean Elders, ambassadors for the oceans that include primatologist Jane Gooddall, filmmaker James Cameron, mogul Richard Branson and musician Neil Young. Earle speaks of “creating a network of hope. The idea is to get people who can weigh in at a level that transcends political boundaries.”

While being fully aware of the damage done, Earle keeps coming back to the positive changes. “This past year, some tangible actions have been taken that are cause for optimism,” she says, referring to the UN Ocean Treaty that aims to protect 30 percent of the oceans by 2030 and the Biodiversity Treaty. “The Biodiversity Treaty recognizes that we’re on a downhill slide to lose at least a million species by the end of this century if we keep doing what we’re doing.”

Earle acknowledges, “We are not currently behaving with that kind of intelligence. We’re using the old model of consuming nature without being concerned about the impact on the next 10 years, the next hundred years, the next thousand years.” However, she points out that the numbers of the California condor and other species, including some whales, who were on the brink of extinction have been successfully restored: “We’ve helped get them back to certainly a better place not where they were 500 years ago, but certainly better than they were 50 years ago.”

When people ask her what they can do to help, the mother of three and grandmother of four tells them to focus on what they love. “You know, we’re causing the problems,” she says. “So we can also cause solutions. You can make change right now, at home. You can make change every day with what you eat, what you wear, with how you vote, with what you plant in your garden if you have access to a yard, with the organizations you join. Would you like to be part of the generation that safeguards our species, safeguards the future of life on earth?”

And of course, anybody can nominate a Hope Spot.

“We should look at this as the best time ever to do something,” Earle insists. “It’s just getting to the point where people realize the urgency. We have to change if we are to survive. It has taken us a very short period of time to begin to seriously unravel the stability of the systems that we absolutely require for our existence. Now imagine if we didn’t know that. That would be a real problem. But we do know now and we know what to do.”

Earle is relentlessly positive when it comes to the future, and the opportunity we have right now to shape it. “That is a reason to be cheerful,” she says. “We know more than ever before at any time in history, and here’s the opportunity to really size up. Where do we want to go? Because we do have choices.”